The ‘mayor’ of St. Clair West: Albert’s Real Jamaican Foods is more than a restaurant, it’s a community hub

By Karon Liu for the Toronto Star

Photo by Steve Russell

Read a follow-up to this piece, “How is Albert’s doing during the COVID-19 crisis?” here.

Thirty-five years ago this month Toronto was in the grips of what the Star dubbed the “Patty Wars,” a 10-day debacle that involved one of Toronto’s most beloved foods, the Jamaican patty.

In 1985, food inspectors served notices to eight Jamaican patty shops in the city because their beef patties didn’t meet the Canadian government’s definition of a beef patty, basically, a burger patty. Shops such as the Kensington Patty Place on Baldwin St. were told to rename their patties to something closer to a meat pie or they would face a $5,000 fine (about $10,600 today). A Feb. 19, 1985, article from the Star included a statement from Ontario opposition leader David Peterson that said, “The federal government’s unilateral decision to force West Indian Canadians to rename their national snack food, the beef patty, is inane.”

Roy Williams, president of the Jamaican Canadian Association, also said in the statement that the patty is “Indigenous” to Jamaicans and that they will “never” give up the patty label. A settlement was eventually reached between the parties and Jamaican businesses were allowed to keep the patty name.

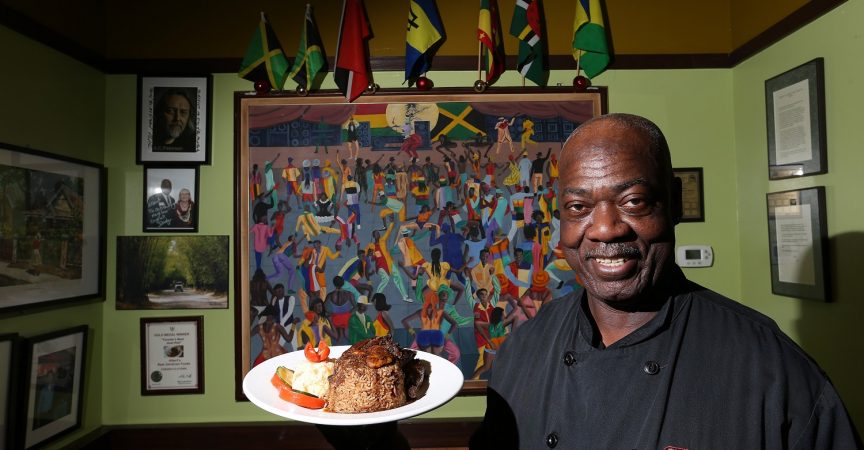

Albert Wiggan doesn’t remember much about the Patty Wars; he was busy running his year-old restaurant at the time, Albert’s Real Jamaican Foods at the corner of St. Clair West and Vaughan Rd. He’s still working at the restaurant today, and at 64, he’s the unofficial mayor of St. Clair West.

For one thing, a laneway was named after him last October. He’s the guy people come to for advice, whether its kids with problems at home or customers asking who to vote for. While talking at the restaurant, he checks his phone because a student was going to interview him for a business project. A woman from the nearby Stop Community Food Centre asks if Wiggan could donate food for an upcoming event. If you try to leave his restaurant without eating, he’ll break out an over-the-top Sopranos impression and say, “I’ve got Italian in my blood” and insist on filling up a takeout box.

The restaurant’s lime green walls are filled with framed letters and awards from local organizations, charities, school boards, business associations as well as the Gov. General. It’s something Wiggan wouldn’t have dreamed of since he moved to Toronto 45 years ago and started working in a factory. But to understand how he got there, he first tells me about his mom.

“My mother Justina had 15 of us. Five of them died at a really young age,” says Wiggan. “My father died when I was two, so my mom was the engine. You couldn’t get away with anything around her, and she expected that when we grew up, we would all know how to cook, sew and iron.”

Growing up in Runaway Bay, a town on the north coast of Jamaica, Wiggan learned to cook rice, stews, soups and chicken dishes to feed his siblings. He later worked in the hotel industry as a waiter and cook. He and his wife, Carolyn, a nurse, moved to Toronto in the mid ’70s, where he worked at a bottle cap factory in Bloordale.

Waves of immigration from Caribbean nations to Canada happened throughout the 20th century. The first being from 1900 to 1960 when Canada’s economy was doing well in the postwar era and many women moved here as domestic workers. The second occurred throughout the ’60s as more than 60,000 Caribbean people came to Canada under the 1962 Immigration Act, which accepted immigrants based on education and skills rather than the previous criteria of race or national origin.

Wiggan’s arrival coincided with what’s considered a third major wave of immigration, as many left Jamaica in the ’70s due to political instability. By then, Toronto had a well-established Jamaican community with local associations, as well as shops and businesses opening along Eglinton Avenue West to form what is now known as Little Jamaica. The latest census data reports that of the 257,060 Jamaicans living in Ontario, just over 200,000 of them live in Toronto, making them one the largest ethnic groups in Toronto.

When Wiggan arrived in Toronto, he says the food at existing Jamaican restaurants didn’t taste like the flavours he knew growing up, so he decided to open his own place. He saved $15,000 from his factory job and through a government loan program he got another $15,000. In 1984, he found a tiny space that charged $1,400 a month rent, at the corner of St. Clair Avenue West and Vaughan Road, southeast of where Little Jamaica was established. He only bought used kitchen equipment to stretch his budget. On the first day, Wiggan says the restaurant made $300 (about $600 today). “It was a lot of work, but we were able to make a deposit at the end of the day,” he says. “We were quite impressed.”

He eventually quit his job at the bottle cap factory after working there for 13 years to focus on the restaurant full-time.

“The hours were long and sometimes I’d have four hours of sleep. I’d sleep on the freezer in the restaurant, go home to take a shower and then come back again,” he says, adding that having severe dyslexia also made running a business challenging. “My wife helped at the restaurant, but she also had a full-time job.”

But word of Wiggan’s cooking eventually reached diners and he began to build a following for his jerk chicken, goat curries and daily soup offerings. He came out with his own line of hot sauces with flavours like mango, pineapple-ginger and cranberry for purchase at the restaurant. A decade ago, he took over the adjoining Coffee Time shop and turned it into the dining room. The old takeout shop space has been converted into the kitchen with tubs of dried beans, bags of rice and a large metal drum to marinate the chicken.

“I used to do this by hand, but I don’t think I could do 1,000 pounds of chicken in three weeks,” he says while showing off the back kitchen. “This kind of cooking isn’t something that you can just throw together. The chicken is marinated overnight using the just right amount of spices: allspice, garlic, seasoning salt, scotch bonnets, there’s a science to creating that flavour.”

It’s something that he wishes more diners would realize when they complain about pricing, even if a complete dinner at Albert’s can cost the same as a cocktail or appetizer at another restaurant.

“Oxtail now costs me $5 a pound because it’s now a more popular ingredient. We give you 12 oz. of oxtail with rice and a salad for $20,” he says, adding that people wouldn’t complain about paying $30 for a 4 oz. piece of steak.

“One of the problems is that Caribbean food is hard to do, but I think it’s underpriced. People may say we’re more expensive, but we compare our food to some of the better restaurants in the city.”

Still, Wiggan says he’s grateful he’s been in business for so long. “I remember people coming here since day one when they were 16, or people who were in their 30s and are now grandparents. People make it a point to come here after taking a trip cause they say our food tastes like home. If you get good food, you’ll always remember it no matter where you go, it stays with you.”

But for him, longevity is more than serving good food, it’s about looking out for the community and showing that even having a disability like dyslexia doesn’t mean life is over. He points to the little flags of countries from around the world that runs along the ceiling above the counter, his indicator that everyone is welcome at the restaurant and proudly states that his employees come from everywhere (one of the cooks rolling dumplings in the back is from Japan, for example).

“What you put into the community is what you get out of it,” says Wiggan. “You reap what you sow, or as my mom used to say, ‘You can’t plant corn and expect to get peas.’”

Albert Wiggan has a line of hot sauces with flavours like mango, pineapple-ginger and cranberry for purchase at the restaurant.

How is Albert’s doing during the COVID-19 crisis?

By Stacey Newman

Things have changed quite a bit since the ‘mayor of St. Clair’ was featured in The Toronto Star, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, we caught up with Albert Wiggan. He says he has seen many things in his life—recessions and the like—and this crisis is just another opportunity to do good.

“One of the most important things in life [is to] put God before everything. Number two, you gotta plant seeds, seeds in people. [This is] very important,” says Wiggan by phone in late May.

He has been on that corner for 36 years, he has met a lot of people. And in those 36 years, Wiggan has planted a lot of seeds, from his heart, not for compensation. He says those people remember that in this situation. They remember the good times and they care.

“You’re put in a position and God knows the reason,” says Wiggan. “A lot of people come here, don’t have money. Food is a gift from God. Money or no money, I feed them all,” and he goes on to say that no one should ever be hungry.

Wiggan credits his mother with his approach to living and building the community. He is the baby of 15 children. He says their mother gave them strong values before they left home. “One of the things she said to me, ‘my son, manners will take you around the world. Respect other people, colour, creed.’” This is how he runs his business and lives his life.

Yes. Wiggan has been hurt by COVID-19. His business is open for takeout and delivery, but then again, running this business has always been difficult. Wiggan suggests the importance of listening to our leaders of Canada, follow what they say, take their guidance, do your best, and be a good person. “I’m not perfect,” says Wiggan. “But at the same time, do unto others as you have them do unto to you.”

Albert’s has received some assistance from the government, which he says came in at just the right time. “We needed that boost, it helped us,” he says.

They are going to be able to keep going through takeout and delivery using SkipTheDishes. Wiggan feels a sense of responsibility, like an essential part of Toronto. He bashfully mentions with a quiet chuckle that they even named a little street after him—Albert Wiggan Lane.

Wiggan is most grateful to his staff. “My success is all about them. My mother always said, ‘you cannot plant corn and get peas, whatever seed you sow is what you will eat,’” and it seems his mother was right.

“Some people have wealth, I have a lot of food. I’m very rich in food,” he says. It is his plan to share this abundance with all the people.