Our Honeyed Future: Canada’s Culinary Consciousness & Pollinator Health

A rich, honey-glazed smoked duck breast. An autumnal side of squash and potatoes with a béarnaise of honey vinegar. Mouthwatering roasted venison with pistachios and honey. A delicate dessert of pear, custard, honey and millet. Canadian menus are bursting with honeyed options. Honey is a starring feature in the present Canadian culinary consciousness, and as a result, so are the hardworking insects—and beekeepers— that bring honey to Canadian tables.

The number of beekeepers in Canada has swelled in recent years. As of 2016, Statistics Canada reported that there were well over 9,800 in operation—a jump of over 1,200 from the year before. These beekeepers, located for the most part in rural areas, mind between 750,000 and 800,000 colonies.

Mylee Nordin is the Program Coordinator and a professor within the newly-created Beekeeping program at Niagara College in Ontario. The three-semester graduate program trains students in such topics as honey bee health and entomology, apiary management, sustainability and commercial beekeeping. Nordin herself learned beekeeping in Manitoba, where she then worked with a commercial beekeeping operation, and later, as a bee inspector. When she moved to Ontario, she was first a staff beekeeper with Toronto Food Share’s Beekeepers Collective and later a bee inspector for Ontario’s Ministry of Agriculture.

Mylee Nordin is the Program Coordinator and a professor within the newly-created Beekeeping program at Niagara College in Ontario. The three-semester graduate program trains students in such topics as honey bee health and entomology, apiary management, sustainability and commercial beekeeping. Nordin herself learned beekeeping in Manitoba, where she then worked with a commercial beekeeping operation, and later, as a bee inspector. When she moved to Ontario, she was first a staff beekeeper with Toronto Food Share’s Beekeepers Collective and later a bee inspector for Ontario’s Ministry of Agriculture.

“I came to beekeeping without a familial past in it, which at the time was very unusual,” says Nordin. “That’s changing. People come to it with lots of different interests. Some people will be interested in the culinary aspect, others are interested in animal behaviour, or in pollinator health, or in the other products of a hive. It’s a fascinating eld that intersects with many other fields of study.”

The first of its kind in eastern Canada, the program is offered through the School of Environmental and Horticultural Studies. It was championed, Nordin says, by the College’s Associate Dean, Al Unwin.

“It all started for [Unwin] with a swarm that ended up in his yard,” says Nordin. “That got the ball rolling.”

“It all started for [Unwin] with a swarm that ended up in his yard,” says Nordin. “That got the ball rolling.”

When the College was first developing the program, says Nordin, they expected interest mostly from those looking to move into large-scale beekeeping operations. “We do have people who are look- ing to establish larger operations,” she says, “but also people who are interested in niche markets, and doing specialized operations, and setting up their own hives and creating their own products, or partnering with other industries.”

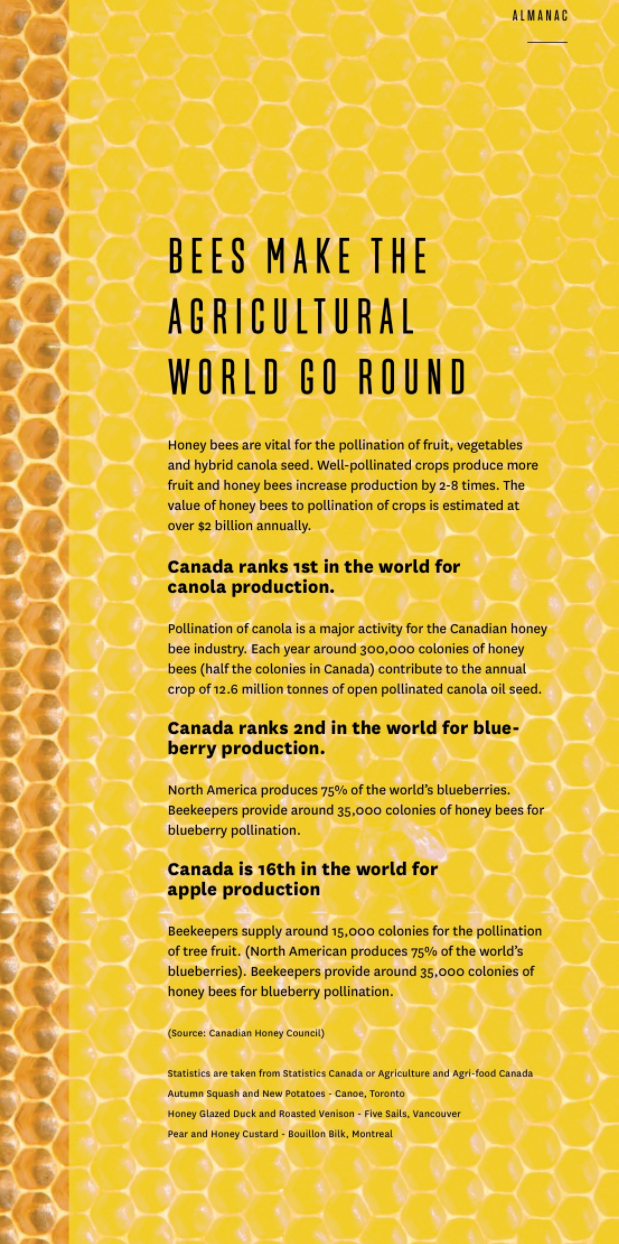

The widespread interest may stem from the fact that bees have been making news in recent years, mostly for their declining populations due to neonicotinoid pesticide use. Now, with bee populations recovering across Canada, the biggest news out of the honey industry is its 13- year low.

Statistics Canada reports a 25% decrease in the value of honey nationally between 2015 and 2016, with decreases in some provinces as high as 35%. The trend has continued into 2017, with alarming lows across the industry.

Statistics Canada reports a 25% decrease in the value of honey nationally between 2015 and 2016, with decreases in some provinces as high as 35%. The trend has continued into 2017, with alarming lows across the industry.

Dani Glennie is on the board of the Canadian Honey Council (CHC) as the representative for Saskatchewan bee- keepers. She says this historic low is the biggest challenge the Council is currently dealing with. “Honey is traded on the national market,” says Glennie. “There happens to be a saturation in the market right now. The price of honey was quite high for a while, and when that happens, companies decide to switch out honey for other products, like corn syrup.”

It’s bad news for an industry with growing numbers of beekeepers needing to move their product to make a living. “If the market doesn’t bounce back soon,” says Glennie, “many beekeepers will be forced to leave this industry. The CHC is doing what we can to help out our bee- keepers. We are actively seeking out new markets and promoting the top-grade honey that we produce here in Canada so that our beekeepers can get the best prices for their hard-earned work.”

One of the biggest hurdles for the CHC, according to Glennie, is that buyers— consumers and foodservice professionals—may not understand the difference between cheap honey and good honey.

“When you read the labels…you just think honey’s honey,” Glennie says. “But it’s not. Cheap honey can be blended with an- other country’s honey, or packers can blend honey with a lesser-quality product.” Even consumers looking to support Canadian beekeepers may be thwarted by mislead- ing packaging that advertises a blend of multi-origin honey as a Canadian product.

The Canadian honey market has limited trading partners. Europe has strict policies when it comes to GMO products, and though honey does not fall into that cate- gory, because it does contain GMO pollens, the EU is against its import. That means the onus is on Canadian buyers when it comes to supporting Canadian beekeepers.

“It’s all about education,” says Glennie. “Knowing that the best honey is produced locally. Wherever you are, if you can buy it from your local beekeeper, that’s the best honey.”

Eating honey has a myriad of benefits. Honey is full of antibodies, is a natural antibiotic—it can even be applied topically to wounds to stave o infection—and eating local honey exposes the consumer to local pollens, which can help control allergies. The CHC has been trying to persuade the Canadian government to change its labelling policies, but the government has recently thrown up a new hurdle: it wants to create special labelling for products— including honey—that are high in sugar. “That would be a huge misrepresentation of honey,” says Glennie. “It doesn’t contain processed sugar at all. All the sugar occur- ring in it is like that of fruits.” A Canadian honey buyer, then, has to be particularly savvy when choosing a product.

When it comes to future trends, Glennie is carefully optimistic: “The market will climb. I do believe the market will move, but will it move in time to keep as many beekeepers as we have in Canada in business?” That’s the question, and until the market does recover, Canadian consumers—individuals as well as businesses— can step up by buying local.

Canadian restaurants who feature honey on their menus—our leaders in educating consumers.

“The more honey they [restaurateurs] buy, the better,” Glennie says. Promoting menus which include dishes made using local, nutritious and natural honey is the sweetest thing that restaurateurs can do to support Canada’s honey producers and pollinator health. “Honey councils are ready to provide assistance and access to current research. Restaurateurs can go to any website of the national, provincial and local honey councils. Many of them list beekeeping operations and restaura- teurs can easily source local honey!” In- formed restaurateurs are on the forefront of supporting Canadian honey producers and informing consumers regarding our national food products.

Canadians enjoy their honey. For bee- keepers and consumers alike, this is an important time to add Canadian honey to the menu.